Sarah Sahim of Pitchfork recently reported on the ‘Unbearable Whiteness of Indie’, noting that ‘In Indie-Rock white is the norm’. Her report has lead to backlash as some artists felt they were being targeted for something beyond their control, as Stuart Murdoch of Belle and Sebastian tweeted in response to the article ‘I wish I was in a band that looked like the Brazil team in the 70s, but we formed in Glasgow’. Although it may be argued that Sahim took the wrong approach in attacking individual bands she has raised a valid issue that applies across the music industry.

Sarah Sahim of Pitchfork recently reported on the ‘Unbearable Whiteness of Indie’, noting that ‘In Indie-Rock white is the norm’. Her report has lead to backlash as some artists felt they were being targeted for something beyond their control, as Stuart Murdoch of Belle and Sebastian tweeted in response to the article ‘I wish I was in a band that looked like the Brazil team in the 70s, but we formed in Glasgow’. Although it may be argued that Sahim took the wrong approach in attacking individual bands she has raised a valid issue that applies across the music industry.The genre of indie music is a clear starting point as it has commonly been associated as a white genre. Looking at the lineups so far for End of the Road festival and Green Man festival the whiteness of the genre is explicit: Out of the acts announced so far only 1 out of 70+ acts for End of the Road are black and 3 acts out of 65+ for Green Man. Yet few seem to question this, purely accepting it as a fact of the genre. A figure that many seem to accept despite his controversial comments surrounding race is Morrissey, one notable example being ‘You can’t help but feel that Chinese people are subhuman’. Many have dismissed Morrisey’s racist behaviour, claiming that his musical ability and popularity outweighs his flaws. However, when it comes to issues surrounding sex people are quicker to speak out. We were ready to talk against Blurred Lines and sexism in the industry but why are people less concerned with race? Why do people find is easier to protect white women but not women (and men) with a different skin colour?

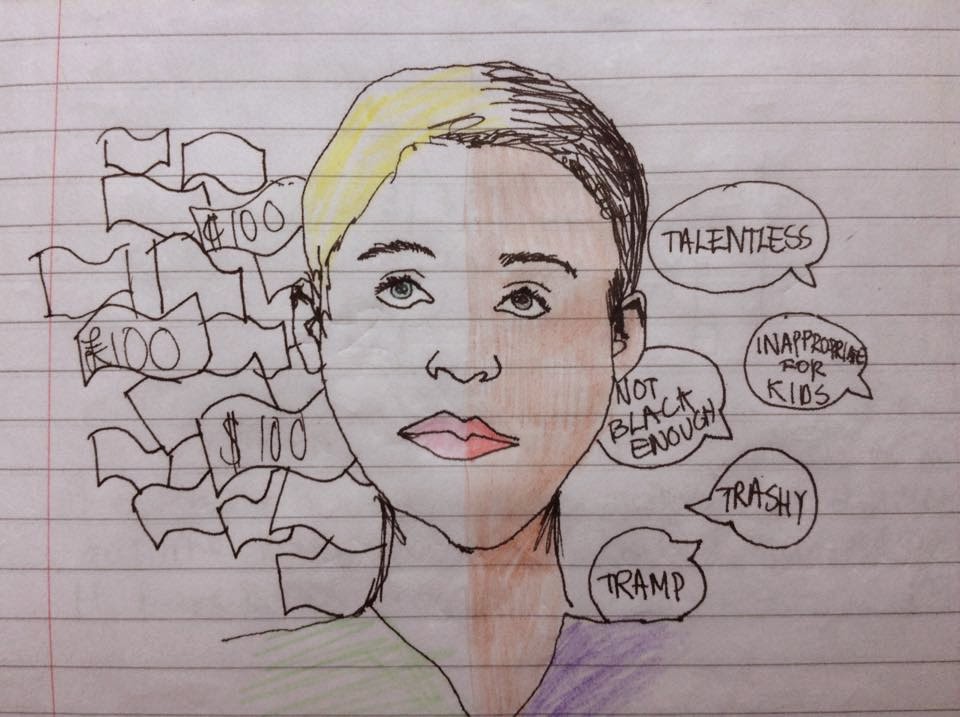

The way we perceive people of different races has highly been influenced by the way they are presented within the industry. In summer 2014 it was reported that ‘White people claim 93% of jobs in UK music and arts industry’. By having such a small minority of other races in a domain where its influence came from them is paradoxical and it also means that people view music from other races as ‘the other’. A clear example of this is black women. In the industry they are rarely given the chance to define their own individuality but are clumped into one group, ‘commonly portrayed as hyper sexual and with a focus and fascinated gaze on their bottoms, invoking ideas of black women as wild and animalistic.’ This attitude to black women is highly toxic because it belittles the message of their work. Nicki Minaj is a clear example of a musician who fell victim, only recently has she been taken seriously for her work which talks about feminism and education as she has had to overcome plenty of criticism surrounding her appearance. Furthermore, she has been listed as one of the many stars (along with Beyoncé) who have been ‘whitewashed’ by magazines to fit into Western beauty standards.

M.I.A is known for her Sri-Lankan Tamil heritage and political activism with lyrics concerning religion and the Sri-Lankan civil war she and her family fled from as she notes ‘some people see planes/ Some people see drones/ Some people see a doom/ And some people see domes’. However, her political messages have been ignored as many have focused on the issue that she doesn’t sound like a ‘typical’ brown girl. In a review of M.I.A.’s debut Arular, Reynolds wrote that while ‘The record sounds great,’ there’s ‘something ever so slightly off-putting about the whole phenomenon...don’t let M.I.A.'s brown skin throw you off: She's got no more real connection with the favela funksters than Prince Harry.’ This is an example of an artist’s style being defined by their skin colour, which should not be relevant. FKA Twigs similarly is popular among indie fans but the label of indie has been removed from her. Instead, she has been placed in ‘PBR&B’, although sounding closer to indie icons Björk and Grimes, not R&B queen Beyoncé. How is it fair to deny people from a music genre or delegitimise their artistic message purely because of the colour of their skin?

Race has been a big issue for men in the industry too. Kayne West was recently announced as headliner for Glastonbury festival and this provoked backlash as 125,000 signed a petition on change.org claiming that he did not deserve it and a rock headliner should be found instead. Many have seen this as a racist issue, because it is placing white rock as superior to black rap and reminds me of Brown’s point that ‘White rock has always been considered as art, and black music as commerce’. Macklemore has also noted that as a white rapper he feels that he has a privilege black artists don't. ‘Why can I cuss on a record, have a parental advisory sticker on the cover of my album, yet parents are still like, 'You're the only rap I let my kids listen to,'’he said. ‘Why can I wear a hoodie and not be labeled a thug?...The privilege that exists in the music industry is just a greater symptom of the privilege that exists in America.’

Music being a microcosm for the society’s political perspective towards race can also been seen through the xenophobic and racist behaviour to ex One Direction member, Zayn Malik. During his time as boy band member Malik was constantly faced with racist behaviour: often labeled as the ‘dark, bad boy’ of the group although there seemed to be no action to go with it, forced to delete Twitter after receiving hundreds of racist tweets calling him a terrorist and had a parody video made about him titled ‘Zayn did 9/11’ which was released on iTunes. Such behaviour was heighten when Malik left the group, with fake reports started by social media that he left to join ISIS.

Only until the white domination of the music industry is over and artists of other ethnicities are no longer made invisible will negative perceptions of race change. We need to stop seeing white music as unique and the epitome of talent, while music of different ethnicities is seen as inferior and lacking authenticity. A musical genre should not be defined by whiteness, as genres can develop and grow to be even better when given diversity.

Written By Enya

Picture Credit: Ellen

No comments:

Post a Comment